CS106L(4): Your brain becomes Streams

What? Streams? The first thing comes into my mind:

Haha…

Core Idea

- Streams

- File Streams

- String Streams

- Buffering

- State Bits

- Chaining

Lecture 4: Streams - Note

View Lecture Note

Streams

A stream is an abstraction for input/output.

Streams can take different types of input, any primitive type can be inserted; for other types, you need to explicitly tell C++ how to do this.

cout << "Strings work!" << endl;

cout << 1729 << endl;

cout << 3.14 << endl;

cout << "Mixed types:" << 1123 << endl;

Streams convert between the string representation of data and the data itself.

Idea: both input and output are strings; need to do computation on object representation. < ???

Types of Streams

Output Streams

- Of type

std::ostream - Can only receive data with the « operator

- Converts data to string and sends it to stream

std::cout << 5 << std::endl; // prints 5 to the console

std::ofstream out("out.txt", std::ofstream::out);

out << 5 << std::endl; // out.txt contains 5

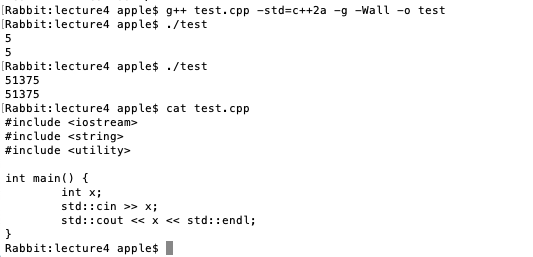

Live Code Demo: Ostreams.cpp ???

Input Streams

int x;

std::cin >> x;

Here, prof asks questions: what happens if input is 5 or 51375, seems nothing different.

-

Of type std::istream

-

Can only give you data with the » operator

- Receives string from stream and converts it to data

-

- to use it, need to include

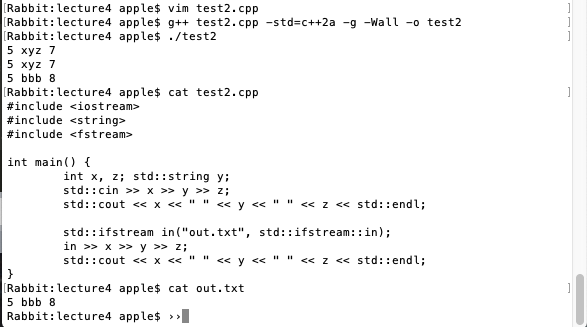

// input: 5 xyz 7

int x, z; string y;

std::cin >> x > y > z; // x=5, y=“xyz”, z=7

// std::ifstream does the same for files

std::ifstream in("out.txt", std::ifstream::in);

in >> x >> y >> z; // out.txt contains 5

Demo code:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <fstream>

int main() {

int x, z; std::string y;

std::cin >> x >> y >> z;

std::cout << x << " " << y << " " << z << std::endl;

std::ifstream in("out.txt", std::ifstream::in);

in >> x >> y >> z;

std::cout << x << " " << y << " " << z << std::endl;

}

Why does this work?

- Think of a

std::istreamas a sequence of characters - Extracting an

intreads as many characters as possible untilwhitespace - Next time, first

skipover any whitespace - When no more data is left, failbit set to true

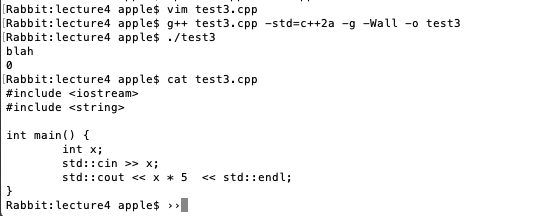

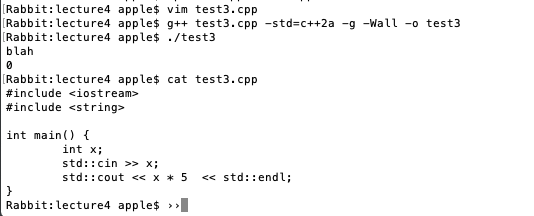

Another Example

int x;

std::cin >> x;

std::cout << x * 5 << std::endl;

// what happens if input is blah ?

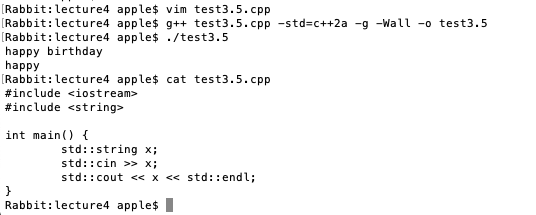

Reading using » extracts a single “word” including for strings

How to read the whole line?

To read a whole line, use getline(istream& stream, string& line);

- Don’t mix » with getline!

>>reads up to the next whitespace character and does not go past that whitespace character.- getline reads up to the next delimiter (by default, ‘\n’), and does go past that delimiter.

- Don’t mix the two or bad things will happen!

Additional Stream Methods

input.get(ch); // reads a single char

input.clear(); // resets the fail bit

input.open("filename"); // opens stream on a file

input.seekg(0); // rewinds stream to start

input.close(); // closes stream, done automatically for you, can delete

std::iostream

std::iostream is both an istream & ostream.

Stringstreams

Work with a string as if it were a stream.

To use istringstream, need to include .

std::string input = "5 seventy 2";

std::istringstream i(input);

int x; std::string y; int z;

i >> x >> y >> z;

std::cout << z << endl;

Live Code Demo: String Streams

Stream Internals

- Buffering

- State Bits

- Chaining (a.k.a. why « « « works)

Buffering

Writing to console/file is slow. If we had to write each character separately, slow runtime.

So, accumulate characters in a temporary buffer. When full, write entire buffer to output.

input << "hel";

input << "lo ";

input << "world";

Output: hello world

Empty the buffer early by flushing:

stream << std::flush; // flush what we have so far

stream << std::endl; // flush with newline

// this is equivalent to: stream << “\n” << std::flush;

Buffer Takeaways

- The internal sequence of data stored in a stream is called a

buffer. Istreamsuse buffers to store data we haven’t used yet.Ostreamsuse buffers to store data that hasn’t been outputted yet.

Q: There’s actually a third standard stream,

std::cerr, which is not buffered. Why?

Some answers from Internet:

cerr is not unbuffered, it’s unit-buffered, that means it will be

flushed automatically after every output operation.

Because cerr is used for outputting error text, which presumably has to appear immediately, and should also appear even if the program aborts immediately after. Typically (hopefully?) too, there will be very little output on cerr, so the loss of performance doesn’t matter.

State Bits

Streams have four state bits:

Good bit: whether ready for read/writeFail bit: previous operation failed, future operations frozenEOF bit: previous operation reached end of fileBad bit: external integrity error

Using State Bits

Common Read Loop:

while (true) {

stream >> temp; // read data

if (stream.fail()) break; // checks for fail bit OR bad bit

doSomething(temp);

}

Streams can be converted to bool.

stream >> temp;

if (stream.fail()) break; // checks for fail bit OR bad bit

doSomething(temp);

↓

stream >> temp;

if (!stream) break; // same thing

doSomething(temp);

Aside: Chaining

This means setting ref equal to a new value is exactly the same as setting original equal to that value! We can’t change what variable ref aliases.

<<:

std::ostream& operator<<(std::ostream& out, const std::string& s);

operator<<(std::cout, "hello");

>>:

std::ostream& operator>>(std::istream& in, const std::string& s);

operator>>(std::cout, temp);

magic std::cout mixing types

Functions:

std::ostream& operator<<(std::ostream& out, const std::string& s);

std::ostream& operator<<(std::ostream& out, const int& i);

Flows:

cout << "test" << 5;

↓

operator<<(operator<<(cout, "test"), 5);

↓

operator<<(cout, 5);

↓

cout

Using State Bits — Part 2

A very common read loop:

while (true) {

stream >> temp; // read data,this returns the stream itself!

if (!stream) break; // checks for fail bit OR bad bit

doSomething(temp);

}

Based on the returntype, we can make the following code work:

// here’s a very common read loop:

while (stream >> temp) {

doSomething(temp);

}

Haha, congrats, 4th lecture finished! Your brain becomes a stream.